Guarding a Pacific Anglo-Saxon Civilisation

Sir George Grey on the racial make-up of New Zealand and Australia

“It would, therefore, hardly be an exaggeration to say that the future of the islands of the Pacific Ocean depends upon the inhabitants of New Zealand being true to themselves, and preserving uninjured and unmixed that Anglo-Saxon population which now inhabits it, and the pure-bred descendants of which ought to inhabit these islands for all time.”

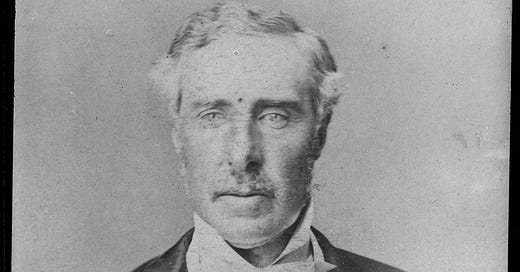

In 1879, the former Governor of New Zealand and then MP, Sir George Grey, had a short paper he wrote regarding the racial/ethnic make-up of New Zealand and Australia published in the Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives. The paper, called ‘(Memorandum on the) Immigration of the Chinese into the Colony’, details Grey’s views on how decisions surrounding immigration, religion and culture would have major impacts on the ‘Anglo-Saxon civilisation’ in the British Pacific colonies. The contents of the paper have been republished here:

Probably people have but little reflected upon the great struggle which must take place in this part of the world against barbarism. Men trust too much to the belief that civilisation is continually and rapidly to advance, and that no retrograde movement or delay in its progress is possible. But if we consider for a short time we shall see that the extension of civilisation throughout the Pacific, and throughout the countries bordering upon it to the North and West, must of necessity be a long and difficult task, and that, unless great care is now exercised, it is even doubtful if civilisation will be able to hold its own against the flood of barbarism which it will have to encounter.

Let us look for a few moments at Australia. A small portion only of that continent can be cultivated by labourers of the European race. It may, indeed, be assumed that the only parts of Australia which are likely to be permanently occupied by European farmers, unassisted by coloured labour, are New South Wales, parts of Queensland, Victoria, the southern parts of South Australia, and the southern parts of Western Australia. Those portions of that country contain, also, large tracts of indifferent land, which could not carry a dense population of European descent.

The tropical portions of Australia contain a vast amount of good land, often communicating with or adjacent to commodious harbours, and traversed by rivers of considerable size. Tropical territories of this kind are capable of carrying a very dense coloured population. Cultivated by people of fitting races, directed by European knowledge and skill, they will yield in abundance commodities of the highest value. The Malay Islands, lying within a few days' sail of that part of the island-continent, can supply not only labour, but horses, cattle, sheep, and provisions to settlements established in North Australia. China can also furnish, in a short time, and without difficulty, an unlimited stream of industrious immigrants, who would be attracted not only by the agricultural capabilities of the country, but by its gold and other mineral resources, which are undoubtedly great.

These and other circumstances render it almost certain that a dense population of various races, and of different degrees of civilisation, will shortly exist in the tropical portions of Australia, possibly in great part employed by European capital and directed by European enterprise. These territories when thus occupied must be ruled from the southern parts of the continent. The whole of the civilisation of the north - its religious faith, its commerce, and the nature of its laws - must all be dependent upon the degree of civilisation that prevails in those portions of Australia in which the Anglo-Saxon race first took root.

Clearly, therefore, the most jealous care should be exercised in securing a constant flow into the existing colonies in the south of Australia of immigrants trained under institutions of the highest political and social character. No possible chance should be allowed to arise of the European population being over-borne, or even to any extent interfered with, by a people of an inferior degree of civilisation. If a mixed race of an inferior order be allowed to spring up and become the ruling power in those Anglo-Saxon colonies, there can be little hope of a high degree of civilisation ever prevailing throughout Australia as a whole.

A greater interest, however, than that of Australia itself is involved in this question. The islands to the north of that continent, and the great kingdoms which also lie to the north of it, must be hereafter largely influenced by the degree of civilisation which prevails in Australia. The happiness and welfare of the many millions of people who inhabit those countries are therefore deeply involved in the future of Australia. For, if the Anglo-Saxon becomes the ruling race in this portion of the world, its faith, its civilisation, its laws, and its language will, in the lapse of years, be paramount in all those countries contained in or bordering on the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Hence will arise bonds which will help to bind together the Anglo-Saxon race throughout all portions of the globe which they inhabit or control. This, also, would unite the greater part of the world and of the human family by ties and common interests calculated to prevent wars, to promote commerce, literature, and learning, and to call into existence a prosperity and contentment such as no former age of the world has known.

To preserve, therefore, the Anglo-Saxon race in its full purity in the southern parts of Australia is not a mere selfish instinct. The good of many millions requires that no false step be taken, such as at this early period of their history would mar and render impossible the bright future which lies before those colonies and this portion of the world.

If we turn to New Zealand we shall find that the same line of reasoning holds good. The welfare of the Pacific and the adjacent countries depends still more upon New Zealand than upon Australia. New Zealand is in an isolated position in the Pacific Ocean. It has not near it vast masses of uncivilised people. Every portion of it can be inhabited and cultivated by Anglo-Saxons. Small farmers and their families may thrive in every part of it. And it can, by reason of its climate and fertility, carry a very numerous population in a highly civilised condition. The first immigrants to New Zealand were selected with extraordinary care. Thus the foundations for the future nation were here most wisely laid.

With a soil generally fertile, New Zealand abounds in coal, minerals, forests, and excellent harbours. Its climate is one of the finest in the world. These advantages will enable it to support a numerous people. Its children, brought up in a temperate climate, amidst mountains and forests, or accustomed from youth to the sea, must form an athletic and healthy race. Trained also under free institutions, and accustomed to obey the dictates of Christianity, they will be capable worthily to govern and direct the commerce and civilisation of the numerous islands which lie to the east and north of their country. It would, therefore, hardly be an exaggeration to say that the future of the islands of the Pacific Ocean depends upon the inhabitants of New Zealand being true to themselves, and preserving uninjured and unmixed that Anglo-Saxon population which now inhabits it, and the pure-bred descendants of which ought to inhabit these islands for all time.

It is necessary to remember that the greater number of the islands in the Pacific Ocean cannot be inhabited permanently by a European race. They must be inhabited and cultivated by people who, in the first instance, will be either barbarous or of an inferior order of civilisation, and unaccustomed to the Christian faith. The future welfare and progress of those islands, therefore, depends upon their being in the vicinity of a Christian and civilized race, to whom they can look up for example and guidance, by whom they can be governed, whose language they should be encouraged to adopt, whose laws should command their reverence, and who should be felt to be at once their superiors, their friends, and a people worthy of their imitation.

Now, this can only be accomplished by New Zealand possessing a population of a superior character, whose good qualities have been developed by their religion, their laws, their literature, the freedom of their institutions, their commerce, their general prosperity, their happiness and contentment, their attachment to the institutions under which they have grown into a people, and a knowledge of their own worth, and of their capacity for fulfilling the great duty to which they are called. They should, in short, be a people manifestly capable of exercising that vast influence in this portion of the world which appears to be the inheritance appointed for them by Providence. If this is the case, it is thus clearly their duty to themselves, no less than to their neighbours, to take care that they shall always continue fit to work out so great a future. All their institutions are being based upon the supposition that a great destiny lies before them. If they allow themselves to be in any degree embarrassed by foreign races, or if a mixed breed of an inferior degree of civilisation is allowed to spring up here, not only the welfare of the other races who surround them will be imperilled, but their own future will be greatly endangered.

Holding these points in view, let us proceed to some further considerations. The presence in this country of a large population of Chinese, or of any cognate race, would exercise a deteriorating effect upon its civilisation. There can be little doubt that they would largely influence the labour-market. From their habits and mode of life they could subsist upon a much smaller sum than is necessary for the support of a European household in decency and comfort. They could, therefore, work for less wages, and those European artificers or labourers who were thus driven into competition with strangers, and were forced to accept a rate of wages below what the necessities of themselves and their families required, would have to make great sacrifices of their independence and welfare. They would indeed have to descend to the scale of civilisation which their competitors from habit would occupy with satisfaction; whilst to the European, this change in his habits, in his diet, clothing, and dwelling, would involve an entire abnegation of his self-respect and independence. After a few years of suffering, the habits and civilisation of himself and his family would be entirely altered.

The Chinese coming here unaccompanied by females (who are prohibited by the laws of the country from leaving China) would, again, in many respects, exercise a very deteriorating effect upon the Europeans in this country. This is a subject which need not be alluded to at length. Those who choose to think it out, and to follow it into its various ramifications, will find it pregnant with interest, and will, I think, be forced to admit that it must prove prolific in disasters to New Zealand.

There is another circumstance which should be thought of. In all the islands of the Pacific the terrible disease of leprosy exhibits itself from time to time. It has always existed in some degree in the New Zealand Islands, but the Natives formerly kept it almost entirely stamped out by isolating their lepers. Leprosy prevails in China; and wherever the Chinese go in numbers they carry that disease with them. It is stated that their advent into the Sandwich Islands was marked with the great spread of that disease throughout the aboriginal population. It must be borne in mind that, if a large population in a peculiar degree of civilisation is introduced into any country, all the diseases inherent in that population are at the same time introduced with them. The influx of vast masses of coolies into Mauritius introduced many new diseases into that colony. Therefore, not only leprosy but other diseases must be expected to be coincident with the introduction of any large number of Chinese into New Zealand.

The consideration of the arguments used in this paper will show that it is necessary some regulations should be laid down regarding the future immigration of Chinese into this country. Up to the present time about five thousand Chinese have arrived here. Nine females have also been returned as being inhabitants of New Zealand, but they are stated to be not of purely Chinese origin.

There is the more necessity for some such regulations being laid down, because there are circumstances connected with foreign immigrants which render them acceptable to holders of large properties. If located in villages in the vicinity of large properties they give a great value to them, because, being strangers in a foreign country, of the language, laws, and customs of which they know but little, they naturally cling together and do not roam in search of employment; nor do they readily, with the hope of bettering themselves, quit the spot of their first location. Indeed, the very circumstances which render such immigrants of little value for the first few years to the country at large which they have come into, render them peculiarly acceptable to the holders of large properties. But here in New Zealand we want citizens - that is to say, men who can at once add to the wealth of their adopted country, who can take a part in its public affairs, who can intelligently watch the introduction of laws and assist in the administration of them; who, in fact, are interested in the immediate progress and in the future of the country of their adoption - who feel that they are part of a youthful nation. An unwise cry is often raised regarding the wealth and material prosperity of a country. To secure enormous wealth to a few individuals, and to leave the overwhelming majority of the people sunk in penury, is not the true end which should be aimed at by those who desire to see their country raised to real prosperity and greatness.

G. Grey