What does it mean to be a European New Zealander?

A brief overview of NZ European culture.

“Does White NZ have any culture other than constantly talking about WW1?”

These were the words spewed out of the mouth of a real - although racially ambiguous - New Zealander in response to video content displaying pride in European New Zealanders, filled with the usual militaristic bells and whistles. Although anyone familiar with the nationalist scene might scoff at such breathtaking ignorance of New Zealand history, it does bring into question what particular, identifiable culture NZ Europeans have in New Zealand.

In some ways, the racially ambiguous ‘New Zealander’ is correct in that most New Zealanders only have a very surface-level understanding of their own history, most of which is through the yearly ANZAC parades held in their local town centres. There is such a deeply rooted yet ironically fleeting disconnect between European New Zealanders - or perhaps New Zealand as a whole - and their history, their forefathers, their struggles and their lineage. It would be difficult to find any other country on earth where the majority of its largely ethnically uniform population conforms to a culturally cosmopolitan and liberal outlook towards its own past - either through pure ignorance, shame or even hatred.

One of the reasons I set out to create the Zealandia Heritage Foundation with my colleagues was to rectify this underappreciation for New Zealand’s rich history, which is undervalued by the state and the common people alike. From great musical compositions and the free-flowing words of our colonial poet romanticists to the great yet unknown political actors and even the lowly provincial newspaper archives, our history and culture are all there - its tremendous breadth and depth are available for all to see. Still, it takes skill and time to unravel it all. For most European New Zealanders though, the answer to what ‘white NZ’ culture is remains just out of reach.

Therefore, I wanted to make one of the Zealandia Heritage Foundation’s first blog posts on this issue, although it will be dissected and discussed piece by piece in more detail in future posts. To discuss the impacts of race, religion, culture and everything in between without exploring their own individual subparts in their dedicated posts would be disrespectful to both New Zealand as a whole and all those men and women who often spent their whole lives labouring to build a country from nothing.

On the topic of ‘building a country from nothing’, New Zealand was arguably one of the last ‘Terra Nullius’ (nobody’s land) colonies to be established in the mid-19th century. Between Abel Tasman’s discovery of New Zealand in 1642 and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, a plethora of brave men and women alike made landfall on NZ’s shores seeking to establish themselves here. Whether it be in the form of sailors/merchants for profits, adventurers for the thrill/glory or priests to spread the Good News of Jesus Christ, all of them experienced great tribulations - many in the form of death and martyrdom.

Even as settlers began arriving from Britain in an organised fashion from the late 1840s onwards, settlers still experienced raids from local Maori, high infant mortality rates and all the facts of life that come with establishing a new country. Consequently, this collective struggle against tribal conflict and lack of resources that all settlers experienced developed into New Zealand’s pioneering spirit - now known as 'Kiwi ingenuity'. This can-do attitude of ‘doing it yourself’ still exists in NZ European culture today, as Kiwi ingenuity is merely the spiritual successor to the values and experiences of our colonial forefathers.

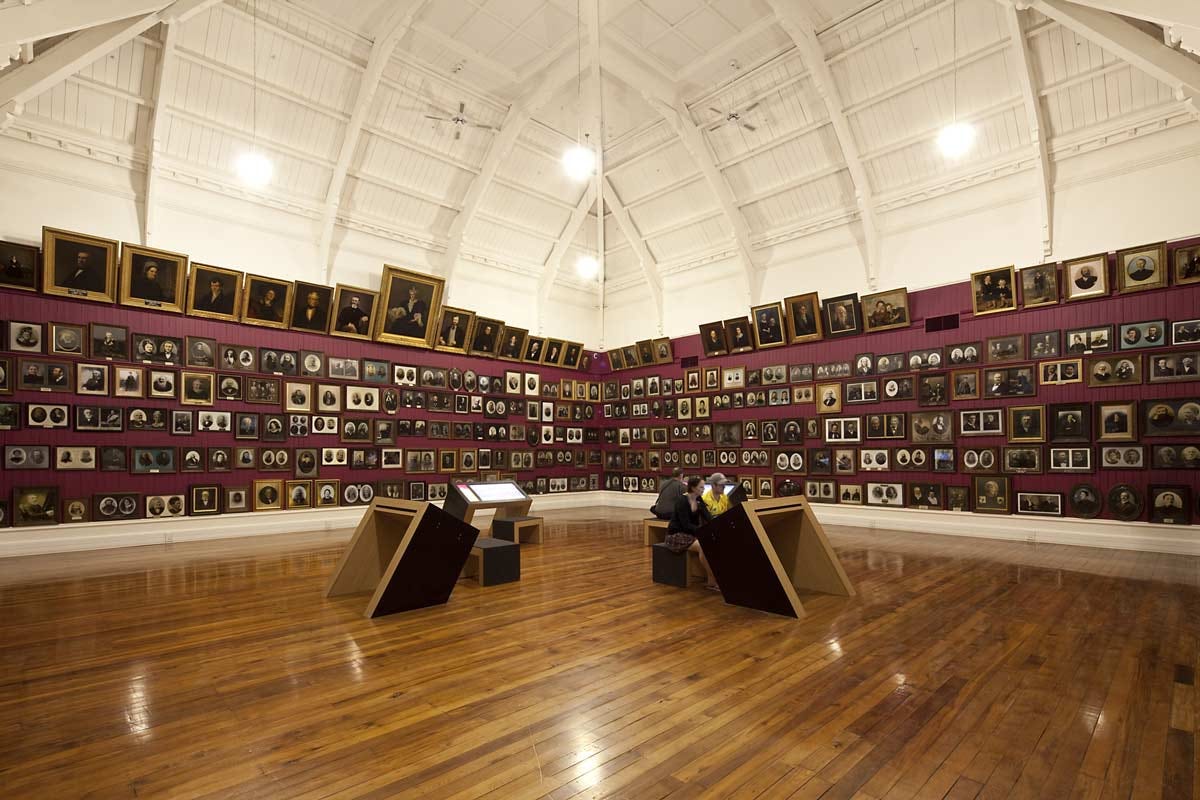

As European settlements grew, New Zealand’s first cities were born with all the grand and unique architecture that came with them. Victorian and subsequent Edwardian/Georgian era New Zealanders left us with a great range of rich heritage buildings, of which many had a unique New Zealand architectural style - from the minute designs of trams and their wire pillars to the breathtaking designs of our cathedrals such as the use of native timber in Wellington’s Old St Paul’s, as well as the sophisticated use of Oamaru stone in Dunedin Railway Station. Whether you live in a provincial town or a major city, when one gazes upon the beauty of our large range of heritage buildings of all styles and purposes on a regular basis but still ask “Does White NZ have any culture?” - it only portrays an astonishing ignorance on behalf of the questioner. Due to the need to walk around outside to view our architecture, it might benefit the original questioner to, as they say, ‘touch grass’.

Although small countries like New Zealand tend to have its artistic spheres like music and writing dominated by the cultural imports of larger nations, NZ has produced much of its own over the years and continues to provide a way for predominantly European New Zealanders to present their livelihoods in the form of song, poem or story. Classical compositions such as the works of Alexander Lithgow represent some high-grade NZ-made works that reflect European culture in New Zealand, with one of his best and most famous marches in the world - Invercargill March - resulting in the immortalisation of his hometown of Invercargill in the eyes of the world. From the country folk music of Garner Wayne and Dusty Spittle to the ANZAC-composed war ballads of the world wars of Walter Impett to the classical/religious music of Alfred Hill and Arthur Carbines, New Zealand has long been able to express its own unique identity through music.

The concept of viewing and listening to music in general also is inherently a European cultural trait. For example, nearly every year since 1857, the city of Auckland has held at least one annual Christmas performance of Handel’s ‘Messiah’ with most of the relatively modern performances taking place in the Auckland Town Hall. Herein lies a great example of culture - audience and musicians in formal European-style dress, using European instruments, performing a song written in European style and it is all performed inside of a large European-style town hall containing all the minute details required to make great architecture. This performance, alongside any performance of New Zealand music, requires an acknowledgement of its intrinsic European-ness and the monumental effort required on behalf of those who created the music, crafted the instruments, designed/tailored the clothing, acquired the materials needed to build the town hall and those that designed and constructed it. A number of analogies can be made on similar things, but such a simple performance of music in a town hall must be recognised for what it is - a glorious show of European (and New Zealand) culture.

Moving away from the more high-class music, we descend into the realm of folk and country music. New Zealand’s first folk song ‘Davy Lowston’ predates NZ's founding by ~25 years and speaks straight from the soul of our origins - as sailors, whalers and sealers. The song speaks of the stranding of a man named David Lawrieston and his remaining crew from the Active, which had been wrecked on the coast of what is now called Jackson Bay - back in 1810. New Zealand’s folk music largely draws inspiration from the history of famous Kiwis, mining, and rural living in general, with singers like Phil Garland and Willow Macky being at the forefront of NZ’s colonial/rural cultural scene. A special mention to Rod Derrett is also in order due to his great talent for producing comedic music relating to everyday topics of New Zealand life during the 1960s, particularly his controversial ‘Puha & Pakeha’ - a song about Maori cannibalism.

As a country with a strong rural identity, New Zealand country music has made its own impressions upon our cultural psyche. Prominent country singers such as Garner Wayne, Danny McGirr, Brendan Dugan and Dusty Spittle - like our folk singers - all sang about the greatness of New Zealand and her history in the form of song. From topics such as famous Kiwi horses like Cardigan Bay, the folk legend James MacKenzie, Southland whiskey bootlegging and even the state of countryside pubs, NZ European country singers have covered them all. Truly, the real heart and soul of New Zealand has been brought forth by our folk and country songwriters.

Transcending from performing arts to the literary arts, New Zealand’s poetic beginnings occurred before the New Zealand Company even landed Europeans on NZ shores. William Golder wrote one of New Zealand’s earliest poems whilst on board the ‘Bengal Merchant’ - one of the first ships to arrive in New Zealand with colonists - with Golder praising the incoming colonisation of New Zealand and the Wakefield Plan:

“Your generations yet unborn shall bless

The time when we your country colonised;

And they again shall to their seed express

Their pleasure at a plan so well devised,

At seeing twofold blessings realised,

From changes which their grandsires have sustain’d,

In days of yore, in being civilised;

And grateful for the favours so obtained,

A mission ’mong their neighb’ring isles shall have maintain’d.”

Since then, Golder’s successors have made countless efforts to express New Zealand’s beauty and spirit in poetic form. In 1890, newspaper editor and poet John L. Kelly paid tribute to Auckland City, writing in the New Zealand Observer:

“Auckland! Queen City of the Austral Seas,

Seated Majestic on thy hundred hills,

Soothed by the murmuring of hidden rills,

And songs of birds embow'red amid the trees;

Sweet home of beauty, whose enchantment fills

With new delight the ever wondering eyes;

Whose genial heat, and cool, refreshing breeze,

And mildly radiant skies

Give endless Summer to the circling year,

Make Nature ever gay and life for ever dear!

The Past is thine; thy fortunes and thy fame

Are with Zealandia's story intertwined;

So long as Britons bear the Past in mind

So long shall live the lustre of thy name!

Historic spot, in memory enshrined

As primal ruler of these noble lands;

'Mid toils and trials, men of lofty aim

Laid here, with skilful hands,

The firm foundation of the infant State,

Which grows beneath our eye, enduring, good and great.”

The list goes on. Although New Zealand has not produced any truly great writers on the level of J.R.R. Tolkien or Charles Dickens, there have been a few humbling examples of Kiwi writers that have brought out the weird and wonderful of New Zealand thought on paper. To name a few, Frederick E. Maning’s ‘Old New Zealand’ is a personal favourite of mine and reflects his firsthand experience of being a pre-Treaty European living/fighting/working amongst pre-colonial Maori in a very humorous and well-written memoir. Like ‘Old New Zealand’, there are plenty of written accounts and experiences of settlers that grant us great insight into life in colonial New Zealand.

On the flip side, Edward Tregear’s ‘The Aryan Maori’ is a peculiar book that tries to propose that the Maori people and language are Indo-European - therefore Aryan - and superior to other races. Later, half-Maori anthropologist Sir Peter Buck once remarked that "[Polynesians were] of Caucasian descent and quite distinct from the negroid division of mankind.” While Tregear’s views on anthropology continue to fascinate and inspire discussions around the origin of Maori today, this is a topic for another time.

Circling back to John L. Kelly’s praise of Auckland City, the many different names for our towns/cities reflect the key historical figures involved in the colonisation of New Zealand from afar, those who actively participated in building New Zealand during the colonial era and the often unknown local histories that have impacted what Kiwis call their towns and cities. It’s a common occurrence for both international observers from around the world and New Zealanders here at home to criticise what we call cities like Auckland, and many believe that their names should be changed - perhaps ‘back’ to their ‘original’ Maori names.

The issue here lies with the ignorance of the criticisms, and their inability to recognise the history behind why we call our towns and cities the names we do. New Zealand itself, named after the Dutch province of Zeeland (meaning ‘Sealand’ or ‘Land from the Sea’ in more romantic terms), has quite a prophetic name as most of the continent of Zealandia remains underwater and the name links quite coincidentally with Maori mythology of Maui pulling up the North Island with a fishhook.

Another example, Hamilton was named in honour of the brave Royal Navy officer John F.C. Hamilton, who led a charge against the Maori forces at Gate Pa - dying in the process. The Maori name for Hamilton is Kirikiriroa, after the small Maori village which used to occupy the area before it was largely abandoned during the invasion of the Waikato in the 1860s. The calls to change the name of Hamilton to Kirikiriroa predominantly come from so-called anti-colonial and anti-racist groups who take offence to John Hamilton being the namesake of the city, and as such their desires are inherently anti-European in nature.

The names of our southernmost cities such as Dunedin and Invercargill reflect the Scottish settlers who sought to build up a new, slightly warmer, society predominantly for members of the newly-founded Free Church of Scotland. Dunedin’s name is Gaelic (Dùn Èideann) for Edinburgh, so could be interpreted as being a ‘New Edinburgh’. Invercargill’s name is part Gaelic with Inver coming from the Gaelic word inbhir (meaning the mouth of a river) and Cargill after the first Superintendent (similar to a US governor) of Otago, Captain William Cargill.

The history behind many of our place names like the aforementioned ones represents the living memory of those men and women who helped build New Zealand from nothing, such as the brave John Hamilton, the trailblazing Scottish settlers of Dunedin and the ‘unabashed provincialist’ William Cargill. These names are a part of NZ European culture and heritage, and because NZ Europeans were predominantly responsible for the building of New Zealand and the towns/cities aforementioned, it is entirely within the right of NZ Europeans to maintain the names of their forefathers.

The forefathers of NZ Europeans also brought Christianity to New Zealand. However, religion in New Zealand is a whole topic in and of itself, and it is questionable as to whether or not it is appropriate to plainly lump religion and culture together - particularly as Christianity is a global/universal religion. Although there will be plenty of opportunities to discuss this at greater length in future discussions (as I am certain it will be), the Christian religion has made profound impacts on New Zealand society and culture from a European perspective. It took Christianity nearly eighteen centuries to establish itself in New Zealand, and in the early 17th century the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman aptly named the group of islands at the northernmost tip of New Zealand the ‘Three Kings Islands’, as his ships came upon the islands on the twelfth night of the Epiphany. Although it would take another ~200 years before missionaries began their evangelisation in New Zealand, the name of the Three Kings Islands stood as the first New Zealand place to be named after something Christian - containing a promise of Christ’s light to the Maori tribes.

The first Christian service on New Zealand soil was in 1814 when Samuel Marsden preached his sermon on Christmas day to a group of 400 Maori in the Bay of Islands, both in English and in Maori. Since then, Europeans came to settle in New Zealand and brought with them the cultural and architectural parts of the Christian religion with them, primarily from the Church of England. Although Christianity is a universalist religion that transcends borders and continents, it cannot be denied that European culture was shaped by Christianity and in turn shaped the practice of Christianity - the Anglican Church being the most present example of this.

Even before colonisation began, European missionaries established mission stations across the country to spread the gospel - with missionaries soon becoming adventurers and explorers, discovering both exotic creatures and the pagan habits of the Maori. From then onwards, Christianity has since played a major role in the development of a civilised European society in New Zealand - in many ways it was the Christianisation of the many Maori that encouraged men like Edward Wakefield to promote organised European settlement of New Zealand after the pagan ferocity of the Boyd Massacre in 1809.

Similarly, the struggles of the various missionary societies became synonymous with the general struggles of the European settlers in New Zealand. The righteous missionaries - at great risk to themselves - went far out into the cannibal-filled New Zealand wilderness to “make straight in the desert a highway for our God.” Both settler and missionary suffered at the hands of warring tribes and both became martyrs in the face of pagan fury, particularly from cults like Pai Mārire - who often sought to murder settlers and their families to drive the British back into the sea. Ultimately, their strife is what built New Zealand into the country it is today, and it is their death that proves the everlasting triumph of Christ over these islands.

I want to finish this piece by returning to the original subject matter - “Does White NZ have any culture other than constantly talking about WW1?”. I’m glad to hear that the commenter already agrees that WW1 is a key aspect of NZ’s cultural psyche, especially surrounding the Gallipoli landings in 1915/16. Naturally, all nations are able to rally around some form of common experience, particularly through war, and ANZAC day has time and time again proved to be a solemn ceremony of soldiers marching with their bands in an orderly fashion as politicians make their yearly tributes to New Zealand’s fallen soldiers. While soldiers of all ethnic backgrounds fought and died under the red, white and blue of the New Zealand ensign, it was predominantly European soldiers that perished in the highest numbers - and since the first ANZAC day in 1916, the day has represented the equal opportunity to remember the fallen as well as showing pride in being a part of the British Empire.

In the Auckland Star’s coverage of ANZAC day in 1921, the Anglican Bishop of Auckland (and later Archbishop of New Zealand) in 1921 said: “it was a matter for thankfulness to the civic authorities, the Returned Soldiers’ Association, and all the relatives and friends of our dead heroes that each Anzac Day made a deeper and more solemn appeal to the consciousness and imagination of the citizens of the Dominion to preserve it a day of thankful and thoughtful remembrance of the deeds and heroism that contributed to the coming-of-age of this young and vigorous nation, and its right to claim a place in the ranks of chivalry and knighthood.”

Lest we forget.

So, does ‘White NZ’ truly have any culture other than the First World War? Most certainly, verily, without a doubt - yes. I think it’s an insult to even have to ask the question, and as such it reflects on the stupidity of the person who asked. Go outside!